Sign up for the ControlAir newsletter.

Get news, updates, and offers direct to your inbox.

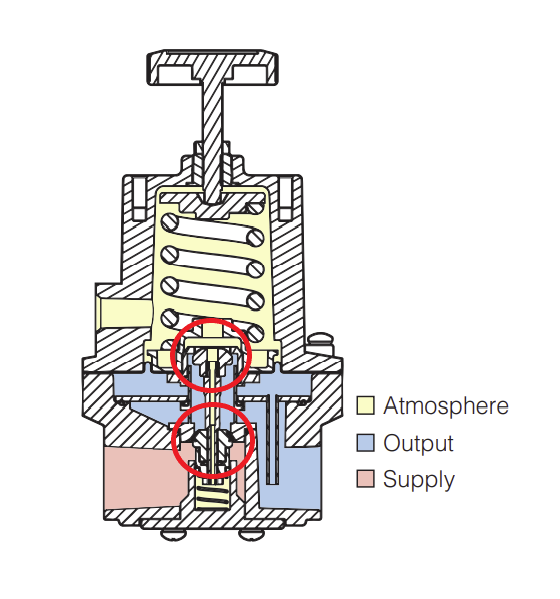

When considering regulator “seats” what we are referencing is the supply or exhaust valve seat that interfaces with the pintle (valve plug) when opening and closing the valve during the process of regulation. In most relieving regulators, there is a valve seat in the supply valve and in the exhaust valve. These areas are circled below on our Type 7000 Precision Air Regulator.

The purpose of this post is to discuss the differences between a regulator with a “soft seat” design and one with a “hard seat” design. This is not necessarily to declare one design as superior over the other as each is well suited for different applications.

Soft seat valves are typically made from softer materials, hence the name, with the most common being rubber. The soft material is beneficial to creating a tight seal ensuring no leakage through the valve. Low pressure range units utilize soft seat supply valves which allow for a tight shut-off and no pressure leakage downstream. The drawback here is that the soft material can be distorted by large amounts of force. This is a factor that can limit the maximum supply pressure of a regulator. The soft material provides a positive shut-off at the supply and exhaust valve which limits, or eliminates, any leakage past the valve. This is useful for limiting fugitive emissions in applications regulating gasses such as natural gas or methane.

The downside to a soft exhaust seat is that it can impact the reactivity and accuracy of a unit. When exhausting, the excess downstream pressure applies an upwards force to the underside of the diaphragm assembly. This lifts the diaphragm assembly and opens the exhaust valve to atmosphere. The pressure is then exhausted until the spring force equals the force of the downstream pressure at which point the exhaust valve is closed. With a soft exhaust seat, the differential between downstream pressure and the regulator setpoint must be greater to fully lift the diaphragm assembly off of the pintle in order to open the supply valve. This can cause downstream over-pressurization as well as “hunting” by the regulator as it tries to settle on a setpoint without over or under-shooting.

While providing a tight seal, a soft supply valve can also cause loss of sensitivity and output pressures higher or lower than desired set pressure due to variability in how the pintle settles on the seat after a disruption such as high flow transition to no flow or supply pressure cycling. The soft seat might cause the pintle to seal prior to the unit rebalancing exactly at set point.

Hard seats are commonly used in designs of the supply and exhaust valve of a regulator. Hard seats are commonly made from plastic but can also be metal in low or high-temperature specific units. Hard seats make a unit much more responsive to changes in pressure in two different ways. First, the exhaust valve may not fully seal and you will experience some “air consumption” by the unit in the form of a small amount of air through the exhaust. This puts the unit into a dynamic and reactive state to provide crisp regulation. You will observe a unit that is more sensitive to system imbalances. Second, when exhausting, the distance that the diaphragm assembly has to travel to open the exhaust valve is smaller when using a hard seat over a soft seat. This allows a hard seat regulator to be very quick to respond when exhausting is necessary and prevents over-pressurization. A soft seat regulator can be described as “mushy” and could overshoot the downstream set point.

Both hard seat and soft seat designs have their advantages and drawbacks. The “better” unit will depend on your application and the level of control or precision necessary.